Sunday, March 31, 2019

Saturday, March 30, 2019

Friday, March 29, 2019

Thursday, March 28, 2019

Wednesday, March 27, 2019

Tuesday, March 26, 2019

All The Pretty Little Horses, Traditional, Performed By Jean Williams

"All the Pretty Little Horses" (also known as "Hush-a-bye") is a traditional lullaby from the United States. It has inspired dozens of recordings and adaptations, as well as the title of Cormac McCarthy's 1992 novel All the Pretty Horses.

The origin of this song is not fully known. The song is commonly thought to be of African-American origin. The author Lyn Ellen Lacy is often quoted as the primary source for the theory that suggests the song was "originally sung by an African American slave who could not take care of her baby because she was too busy taking care of her master's child.

She would sing this song to her master's child".[1] However, Lacy's book Art and Design in Children's Books is not an authority on the heritage of traditional American folk songs, but rather a commentary on the art and design in children's literature.

Still, some versions of "All the Pretty Little Horses" contain added lyrics that make this theory a possibility. One such version of "All the Pretty Little Horses" is provided in Alan Lomax's book American Ballads and Folksongs, though he makes no claim of the song's African-American origins. "Way down yonder, In de medder, There's a po' lil lambie, De bees an' de butterflies, Peckin' out its eyes, De po' lil lambie cried, "Mammy!""[2]

Another version contains the lyrics "Buzzards and flies, Picking out its eyes, Pore little baby crying".[3] The theory would suggest that the lyrics "po' lil lambie cried, "Mammy"" is in reference to the slaves who were often separated from their own families in order to serve their owners.

However, this verse is very different from the rest of the lullaby, suggesting that the verse may have been added later or has a different origin than the rest of the song. The verse also appears in the song "Ole Cow" and older versions of the song "Black Sheep, Black Sheep".[3]

Monday, March 25, 2019

All My Loving, John Lennon, Paul McCartney

"All My Loving" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles, from their second UK album With the Beatles (1963). It was written by Paul McCartney[2] (credited to Lennon–McCartney), and produced by George Martin.

Though not officially released as a single in the United Kingdom or the United States, the song drew considerable radio airplay, prompting EMI to issue it as the title track of an EP.[3] The song was released as a single in Canada, where it became a number one hit.

The Canadian single was imported into the US in enough quantities to peak at number 45 on the US Billboard Hot 100 in April 1964.[4][5]

According to journalist Bill Harry, McCartney thought of the lyrics whilst shaving: "I wrote 'All My Loving' like a piece of poetry and then, I think, I put a song to it later". [6] However, McCartney later told biographer Barry Miles that he wrote the lyrics while on a tour bus and after arriving at the location of the venue he then wrote the music on a piano backstage.[2]

He also said "It was the first song [where] I'd ever written the words first. I never wrote words first, it was always some kind of accompaniment. I've hardly ever done it since either."[2]

The lyrics follow the "letter song" model as used on "P.S. I Love You",[3] the B-side of their first single. McCartney originally envisioned it as a country & western song, and George Harrison added a Nashville-style guitar solo.[2][3] John Lennon's rhythm guitar playing uses quickly strummed triplets similar to "Da Doo Ron Ron" by The Crystals, a song that was popular at the time,[3] and McCartney plays a walking bass line.[7]

Lennon expressed his esteem for the song in his 1980 Playboy interview, saying, "[I]t's a damn good piece of work. ... But I play a pretty mean guitar in back."[8] It has been hypothesized that the piece draws inspiration from the Dave Brubeck Quartet's 1959 song "Kathy's Waltz".[9]

Though not officially released as a single in the United Kingdom or the United States, the song drew considerable radio airplay, prompting EMI to issue it as the title track of an EP.[3] The song was released as a single in Canada, where it became a number one hit.

The Canadian single was imported into the US in enough quantities to peak at number 45 on the US Billboard Hot 100 in April 1964.[4][5]

According to journalist Bill Harry, McCartney thought of the lyrics whilst shaving: "I wrote 'All My Loving' like a piece of poetry and then, I think, I put a song to it later". [6] However, McCartney later told biographer Barry Miles that he wrote the lyrics while on a tour bus and after arriving at the location of the venue he then wrote the music on a piano backstage.[2]

He also said "It was the first song [where] I'd ever written the words first. I never wrote words first, it was always some kind of accompaniment. I've hardly ever done it since either."[2]

The lyrics follow the "letter song" model as used on "P.S. I Love You",[3] the B-side of their first single. McCartney originally envisioned it as a country & western song, and George Harrison added a Nashville-style guitar solo.[2][3] John Lennon's rhythm guitar playing uses quickly strummed triplets similar to "Da Doo Ron Ron" by The Crystals, a song that was popular at the time,[3] and McCartney plays a walking bass line.[7]

Lennon expressed his esteem for the song in his 1980 Playboy interview, saying, "[I]t's a damn good piece of work. ... But I play a pretty mean guitar in back."[8] It has been hypothesized that the piece draws inspiration from the Dave Brubeck Quartet's 1959 song "Kathy's Waltz".[9]

Sunday, March 24, 2019

Saturday, March 23, 2019

Blowin In The Wind, Bob Dylan

"Blowin' in the Wind" is a song written by Bob Dylan in 1962 and released as a single and on his album The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan in 1963. Although it has been described as a protest song, it poses a series of rhetorical questions about peace, war, and freedom.

The refrain "The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind" has been described as "impenetrably ambiguous: either the answer is so obvious it is right in your face, or the answer is as intangible as the wind".[2] In 1994, the song was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame. In 2004, it was ranked number 14 on Rolling Stone magazine's list of the "500 Greatest Songs of All Time".

Origins and initial response Dylan originally wrote and performed a two-verse version of the song; its first public performance, at Gerde's Folk City on April 16, 1962, was recorded and circulated among Dylan collectors. Shortly after this performance, he added the middle verse to the song.

Some published versions of the lyrics reverse the order of the second and third verses, apparently because Dylan simply appended the middle verse to his original manuscript, rather than writing out a new copy with the verses in proper order.[3] The song was published for the first time in May 1962, in the sixth issue of Broadside, the magazine founded by Pete Seeger and devoted to topical songs.[4]

The theme may have been taken from a passage in Woody Guthrie's autobiography, Bound for Glory, in which Guthrie compared his political sensibility to newspapers blowing in the winds of New York City streets and alleys. Dylan was certainly familiar with Guthrie's work; his reading of it had been a major turning point in his intellectual and political development.[5]

In June 1962, the song was published in Sing Out!, accompanied by Dylan's comments: There ain't too much I can say about this song except that the answer is blowing in the wind. It ain't in no book or movie or TV show or discussion group. Man, it's in the wind — and it's blowing in the wind. Too many of these hip people are telling me where the answer is but oh I won't believe that. I still say it's in the wind and just like a restless piece of paper it's got to come down some ... But the only trouble is that no one picks up the answer when it comes down so not too many people get to see and know ... and then it flies away. I still say that some of the biggest criminals are those that turn their heads away when they see wrong and know it's wrong. I'm only 21 years old and I know that there's been too many ... You people over 21, you're older and smarter.[6]

Dylan recorded "Blowin' in the Wind" on July 9, 1962, for inclusion on his second album, The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan, released in May 1963. In his sleeve notes for The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961–1991, John Bauldie wrote that Pete Seeger first identified the melody of "Blowin' in the Wind" as an adaptation of the old African-American spiritual "No More Auction Block/We Shall Overcome".

According to Alan Lomax's The Folk Songs of North America, the song originated in Canada and was sung by former slaves who fled there after Britain abolished slavery in 1833. In 1978, Dylan acknowledged the source when he told journalist Marc Rowland: "'Blowin' in the Wind' has always been a spiritual. I took it off a song called 'No More Auction Block' – that's a spiritual and 'Blowin' in the Wind' follows the same feeling."[7] Dylan's performance of "No More Auction Block" was recorded at the Gaslight Cafe in October 1962, and appeared on The Bootleg Series Volumes 1–3 (Rare & Unreleased) 1961–1991.

The critic Michael Gray suggested that the lyric is an example of Dylan's incorporation of Biblical rhetoric into his own style. A particular rhetorical form deployed time and again in the New Testament and based on a text from the Old Testament book of Ezekiel (12:1–2) is: "The word of the Lord came to me: 'Oh mortal, you dwell among the rebellious breed. They have eyes to see but see not; ears to hear, but hear not."

In "Blowin' in the Wind", Dylan transforms this into "Yes'n' how many ears must one man have ...?" and "Yes' n' how many times must a man turn his head / Pretending he just doesn't see?"[8] "Blowin' in the Wind" has been described as an anthem of the civil rights movement.[9] In Martin Scorsese's documentary on Dylan, No Direction Home, Mavis Staples expressed her astonishment on first hearing the song and said she could not understand how a young white man could write something that captured the frustration and aspirations of black people so powerfully.

Sam Cooke was similarly deeply impressed by the song, incorporating it into his repertoire soon after its release (a version would be included on Sam Cooke at the Copa), and being inspired by it to write "A Change Is Gonna Come".[10][11]

"Blowin' in the Wind" was first covered by The Chad Mitchell Trio, but their record company delayed release of the album containing it because the song included the word death, so the trio lost out to Peter, Paul and Mary, who were represented by Dylan's manager, Albert Grossman. The single sold a phenomenal 300,000 copies in the first week of release and made the song world-famous. On August 17, 1963, it reached number two on the Billboard pop chart, with sales exceeding one million copies. Peter Yarrow recalled that, when he told Dylan he would make more than $5,000 (equivalent to $41,000 in 2018[12]) from the publishing rights, Dylan was speechless.[13]

Peter, Paul and Mary's version of the song also spent five weeks atop the easy listening chart. The critic Andy Gill wrote, "Blowin' in the Wind" marked a huge jump in Dylan's songwriting. Prior to this, efforts like "The Ballad of Donald White" and "The Death of Emmett Till" had been fairly simplistic bouts of reportage songwriting.

"Blowin' in the Wind" was different: for the first time, Dylan discovered the effectiveness of moving from the particular to the general. Whereas "The Ballad of Donald White" would become completely redundant as soon as the eponymous criminal was executed, a song as vague as "Blowin' in the Wind" could be applied to just about any freedom issue. It remains the song with which Dylan's name is most inextricably linked, and safeguarded his reputation as a civil libertarian through any number of changes in style and attitude.[14]

Dylan performed the song for the first time on television in the UK in January 1963, when he appeared in the BBC television play Madhouse on Castle Street.[15] He also performed the song during his first national US television appearance, filmed in March 1963, a performance made available in 2005 on the DVD release of Martin Scorsese's PBS television documentary on Dylan, No Direction Home.

An allegation that the song was written by a high-school student named Lorre Wyatt and subsequently purchased or plagiarised by Dylan before he gained fame was reported in an article in Newsweek magazine in November 1963. The plagiarism claim was eventually shown to be untrue.[16][17]

Friday, March 22, 2019

Both Sides Now, Joni Mitchell And Judy Collins

"Both Sides, Now" is one of the best-known songs of Canadian singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell. First recorded by Judy Collins, it appeared on the U.S. singles chart during the fall of 1968.

The next year it was included on Mitchell's album Clouds (which was named after a lyric from the song). It has since been recorded by dozens of artists, including Frank Sinatra, Willie Nelson and Herbie Hancock. Mitchell herself re-recorded the song, with an orchestral arrangement, on her 2000 album Both Sides Now.

In 2004, Rolling Stone ranked "Both Sides, Now" at #171 on its list of The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.[1]

Mitchell is said to have written "Both Sides, Now" in March 1967, inspired by a passage in Henderson the Rain King, a 1959 novel by Saul Bellow. I was reading Saul Bellow's Henderson the Rain King on a plane and early in the book Henderson the Rain King is also up in a plane. He's on his way to Africa and he looks down and sees these clouds.

I put down the book, looked out the window and saw clouds too, and I immediately started writing the song. I had no idea that the song would become as popular as it did.[2][3] However, "Both Sides, Now" appears in the album "Joni Mitchell: Live at the Second Fret 1966" (2014, All Access Records, AACD0120), a live performance on November 17, 1966, from The Second Fret in Philadelphia, PA, which was broadcast live by WRTI, Temple University's radio station. This suggests that Mitchell wrote the song before March 1967.

"Both Sides, Now" is written in F-sharp major. Mitchell used a guitar tuning of E–B–E–G♯–B–E with a capo at the second fret. The song uses a modified I–IV–V chord progression.[4]

Shortly after Mitchell wrote the song, Judy Collins recorded the first commercially released version for her 1967 Wildflowers album. In October 1968 the same version was released as a single, reaching #8 on the U.S. pop singles charts by December.

It reached #6 in Canada.[5] In early 1969 it won a Grammy Award for Best Folk Performance.[6] The record peaked at #3 on Billboard's Easy Listening survey and "Both Sides, Now" has become one of Collins' signature songs.

Mitchell disliked Collins' recording of the song, despite the publicity that its success generated for Mitchell's own career.[7]

The Collins version is featured as the end title music of the 2018 supernatural horror film Hereditary and in the first teaser trailer for Toy Story 4.[citation needed]

Thursday, March 21, 2019

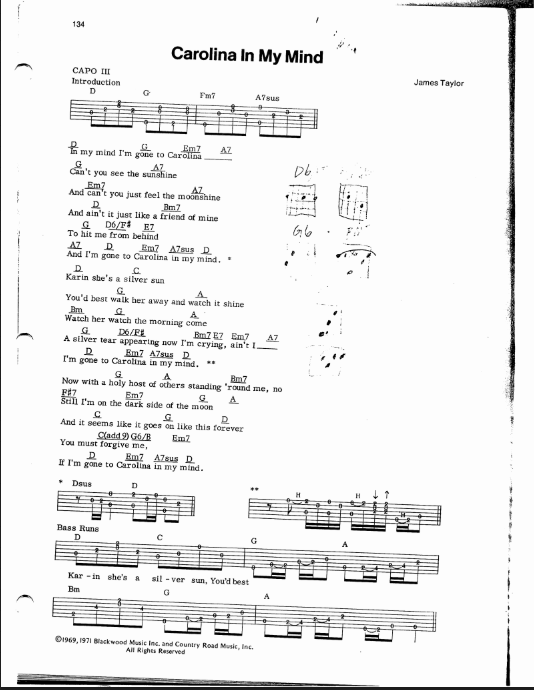

Carolina On My Mind, James Taylor

"Carolina in My Mind" is a song written and performed by singer-songwriter James Taylor, which first appeared on his 1968 self-titled debut album. Taylor wrote it while overseas recording for the Beatles' label Apple Records, and the song's themes reflect his homesickness at the time.

Released as a single, the song earned critical praise but not commercial success. It was re-recorded for Taylor's 1976 Greatest Hits album in the version that is most familiar to listeners. It has been a staple of Taylor's concert performances over the decades of his career.

The song was a modest hit on the country charts in 1969 for North Carolinian singer George Hamilton IV. Strongly tied to a sense of geographic place, "Carolina in My Mind" has been called an unofficial state anthem for North Carolina. It is also an unofficial song of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, being played at athletic events and pep rallies and sung by the graduating class at every university commencement.

The association of the song with the state is also made in written works of both fiction and non-fiction. It has become one of Taylor's most critically praised songs[2][3] and one that has great popularity and significance for his audience.[2] The song references Taylor's years growing up in North Carolina.[4] Taylor wrote it while overseas recording for the Beatles' label Apple Records.

He started writing the song at producer Peter Asher's London flat on Marylebone High Street, resumed work on it while on holiday on the Mediterranean island of Formentera, and then completed it while stranded on the nearby island of Ibiza with Karin, a Swedish girl he had just met.[2][5] The song reflects Taylor's homesickness at the time,[6] as he was missing his family, his dog and his state.[5] Dark and silent late last night,

I think I might have heard the highway calling ...

Geese in flight and dogs that bite

And signs that might be omens say I'm going,

I'm going I'm gone to Carolina in my mind.

The original recording of the song was done at London's Trident Studios during the July to October 1968 period, and was produced by Asher.[7] The song's lyric "holy host of others standing around me" makes reference to the Beatles, who were recording The Beatles in the same studio where Taylor was recording his album.[4] Indeed, the recording of "Carolina in My Mind" includes a credited appearance by Paul McCartney on bass guitar[8] and an uncredited one by George Harrison on backing vocals.[4]

The other players were Freddie Redd on organ, Joel "Bishop" O'Brien on drums, and Mick Wayne providing a second guitar alongside Taylor's.[7] Taylor and Asher also did backing vocals and Asher added a tambourine.[7] Richard Hewson arranged and conducted a string part;[7] an even more ambitious 30-piece orchestra part was recorded but not used.[4]

The song itself earned critical praise, with Jon Landau's April 1969 review for Rolling Stone calling it "beautiful" and one of the "two most deeply affecting cuts" on the album and praising McCartney's bass playing as "extraordinary".[9] Taylor biographer Timothy White calls the song "the album's quiet masterpiece."[4] In a 50-years-later retrospective of the album's release, Billboard calls the song "a mellow Taylor classic" and a "stone-classic".[10]

Released as a single, the song earned critical praise but not commercial success. It was re-recorded for Taylor's 1976 Greatest Hits album in the version that is most familiar to listeners. It has been a staple of Taylor's concert performances over the decades of his career.

The song was a modest hit on the country charts in 1969 for North Carolinian singer George Hamilton IV. Strongly tied to a sense of geographic place, "Carolina in My Mind" has been called an unofficial state anthem for North Carolina. It is also an unofficial song of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, being played at athletic events and pep rallies and sung by the graduating class at every university commencement.

The association of the song with the state is also made in written works of both fiction and non-fiction. It has become one of Taylor's most critically praised songs[2][3] and one that has great popularity and significance for his audience.[2] The song references Taylor's years growing up in North Carolina.[4] Taylor wrote it while overseas recording for the Beatles' label Apple Records.

He started writing the song at producer Peter Asher's London flat on Marylebone High Street, resumed work on it while on holiday on the Mediterranean island of Formentera, and then completed it while stranded on the nearby island of Ibiza with Karin, a Swedish girl he had just met.[2][5] The song reflects Taylor's homesickness at the time,[6] as he was missing his family, his dog and his state.[5] Dark and silent late last night,

I think I might have heard the highway calling ...

Geese in flight and dogs that bite

And signs that might be omens say I'm going,

I'm going I'm gone to Carolina in my mind.

The original recording of the song was done at London's Trident Studios during the July to October 1968 period, and was produced by Asher.[7] The song's lyric "holy host of others standing around me" makes reference to the Beatles, who were recording The Beatles in the same studio where Taylor was recording his album.[4] Indeed, the recording of "Carolina in My Mind" includes a credited appearance by Paul McCartney on bass guitar[8] and an uncredited one by George Harrison on backing vocals.[4]

The other players were Freddie Redd on organ, Joel "Bishop" O'Brien on drums, and Mick Wayne providing a second guitar alongside Taylor's.[7] Taylor and Asher also did backing vocals and Asher added a tambourine.[7] Richard Hewson arranged and conducted a string part;[7] an even more ambitious 30-piece orchestra part was recorded but not used.[4]

The song itself earned critical praise, with Jon Landau's April 1969 review for Rolling Stone calling it "beautiful" and one of the "two most deeply affecting cuts" on the album and praising McCartney's bass playing as "extraordinary".[9] Taylor biographer Timothy White calls the song "the album's quiet masterpiece."[4] In a 50-years-later retrospective of the album's release, Billboard calls the song "a mellow Taylor classic" and a "stone-classic".[10]

Wednesday, March 20, 2019

Carry It On, Words and Music By Gil Turner, Joan Baez And Judy Collins Perform, Watch Watch Benny "Kid" Paret Die...

Carry It On is a 1971 album by Joan Baez, a soundtrack album to the documentary film of the same name. Its title is taken from one of its songs, "Carry It On", which was written by Gil Turner. The film chronicles the events taking place in the months immediately before the incarceration of Joan's husband at the time, David Harris, in 1969.

Gil Turner (born Gilbert Strunk; May 6, 1933 – September 23, 1974) was an American folk singer-songwriter, magazine editor, Shakespearean actor, political activist, and for a time, a lay Baptist preacher.[3] Turner was a prominent figure in the Greenwich Village scene of the early 1960s, where he was master of ceremonies at New York's leading folk music venue, Gerde's Folk City, as well as co-editor of the protest song magazine Broadside.[4][5]

He also wrote for Sing Out!, the quarterly folk music journal.[6] Turner was a founding member of The New World Singers in 1962 with Happy Traum and Bob Cohen.[7][8]

His most notable musical credit, however, was his association with Bob Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind". He was both the first person to perform the song - at Gerde's on April 16, 1962, the night Dylan completed it - and with The New World Singers, the first to record it.[2][9][10]

Turner wrote more than 100 songs. His best known include "Benny 'Kid' Paret", a protest song about a boxer who died in the ring, and "Carry It On", a Civil Rights anthem recorded by folk artists such as Judy Collins and Joan Baez. The song's title was used as the name of a 1970 documentary starring Baez and her husband at the time, draft resister David Harris.[11][12]

Last fight and death Main article: Benny Paret vs. Emile Griffith III Although Paret had been battered in the two fights with Griffith and the fight with Fullmer, he decided that he would defend his title against Griffith three months after the Fullmer fight. Paret-Griffith III was booked for Madison Square Garden on Saturday, March 24, 1962, and was televised live by ABC.

In round six Paret nearly knocked out Griffith with a multi punch combination but Griffith was saved by the bell.[5] In the twelfth round of the fight Don Dunphy, who was calling the bout for ABC, remarked, "This is probably the tamest round of the entire fight."[6] Seconds later, Griffith backed Paret into the corner and unleashed a massive flurry of punches to the champion's head.[7] It quickly became apparent that Paret was dazed by the initial shots and could not defend himself, but referee Ruby Goldstein allowed Griffith to continue his assault.

Finally, after twenty-nine consecutive punches which knocked Paret through the ropes at one point, Goldstein stepped in and called a halt to the bout.[8] Paret collapsed in the corner from the barrage of punches (initially thought to be from exhaustion), fell into a coma, and died ten days later at Roosevelt Hospital in Manhattan from massive brain hemorrhaging.[5][9][10] Paret was buried at Saint Raymond's Cemetery in the borough of the Bronx in New York City.

The last fight between Paret and Griffith was the subject of many controversies. It is theorized that one of the reasons Paret died was that he was vulnerable due to the beatings he took in his previous three fights, all of which happened within twelve months of each other. New York State boxing authorities were criticized for giving Paret clearance to fight just several months after the Fullmer fight.

The actions of Paret at the weigh in before his final fight have come under scrutiny. It is alleged that Paret taunted Griffith by calling him maricón (Spanish slang for "faggot").[7] Griffith wanted to fight Paret on the spot but was restrained. Griffith would come out as bisexual in his later years, but in 1962 allegations of homosexuality were considered fatal to an athlete's career and a particularly grievous insult in the culture both fighters came from.

The referee Ruby Goldstein, a respected veteran, came under criticism for not stopping the fight sooner. It has been argued that Goldstein hesitated because of Paret's reputation of feigning injury and Griffith's reputation as a poor finisher.[5][8] Another theory is that Goldstein was afraid that Paret's supporters would riot.[8]

The incident, combined with the death of Davey Moore a year later for a different injury in the ring, would cause debate as to whether boxing should be considered a sport. Boxing would not be televised on a regular basis again until the 1970s.[11]

The fight marked the end of Goldstein's long and respected career as a referee, as he was unable to find work after that.[citation needed] The fight was the centerpiece of a 2005 documentary entitled Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story. At the end of the documentary Griffith who has harbored guilt over the incident over the years is introduced to Paret's son. The son embraced Griffith and told him he was forgiven.[11]

Tuesday, March 19, 2019

City Of New Orleans Written By Steve Goodman, Performed By Johnny Cash & Arlo Guthrie

"City of New Orleans" is a folk song written by Steve Goodman (and first recorded for Goodman's self-titled 1971 album), describing a train ride from Chicago to New Orleans on the Illinois Central Railroad's City of New Orleans in bittersweet and nostalgic terms.

Goodman got the idea while traveling on the Illinois Central line for a visit to his wife's family. The song has been recorded by numerous artists both in the US and Europe, including two major hit versions: first by Arlo Guthrie in 1972, and later by Willie Nelson in 1984.

While at the Quiet Knight bar in Chicago, Goodman saw Arlo Guthrie and asked to be allowed to play a song for him. Guthrie grudgingly agreed, on the condition that if Goodman bought him a beer, Guthrie would listen to him play for as long as it took to drink the beer.[2] Goodman played "City of New Orleans", which Guthrie liked enough that he asked to record it.

The song was a hit for Guthrie on his 1972 album Hobo's Lullaby, reaching #4 on the Billboard Easy Listening chart and #18 on the Hot 100 chart; it would prove to be Guthrie's only top-40 hit and one of only two he would have on the Hot 100 (the other was a severely shortened and rearranged version of his magnum opus "Alice's Restaurant", which hit #97).

Monday, March 18, 2019

Sunday, March 17, 2019

Copper Kettle, Written by Albert Frank Beddoe, Performed By Joan Baez and Bobby Womak

"Copper Kettle" (also known as "Get you a Copper Kettle", "In the pale moonlight") is a song composed by Albert Frank Beddoe and made popular by Joan Baez. Pete Seeger's account dates the song to 1946, mentioning its probable folk origin,[1] while in a 1962 Time readers column A. F. Beddoe says[2] that the song was written by him in 1953 as part of the folk opera Go Lightly, Stranger. The song praises the good aspects of moonshining as told to the listener by a man whose "daddy made whiskey, and granddaddy did too". The line "We ain't paid no whiskey tax since 1792" alludes to an unpopular tax imposed in 1791 by the fledgling U.S. Federal Government. The levy provoked the Whiskey Rebellion and generally had a short life, barely lasting until 1803. Enjoyable lyrics and simple melody turned "Copper Kettle" into a popular folk song. And here is a completely different version by Bobby Womack

Saturday, March 16, 2019

Sitting On The Dock Of The Bay, Steve Crocker And Otis Redding Performed by Otis Redding

"(Sittin' On) The Dock of the Bay" is a song co-written by soul singer Otis Redding and guitarist Steve Cropper. It was recorded by Redding twice in 1967, including once just days before his death in a plane crash.

The song was released on Stax Records' Volt label in 1968,[2] becoming the first posthumous single to top the charts in the US.[3] It reached number 3 on the UK Singles Chart.

Redding started writing the lyrics to the song in August 1967, while sitting on a rented houseboat in Sausalito, California.

He completed the song with the help of Cropper, who was a Stax producer and the guitarist for Booker T. & the M.G.'s. The song features whistling and sounds of waves crashing on a shore.

Friday, March 15, 2019

Don't Think Twice, It's All Right, Bob Dylan

"Don't Think Twice, It's All Right" is a song written by Bob Dylan in 1962, recorded on November 14 that year, and released on the 1963 album The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan and as a single.

In the liner notes to the original release, Nat Hentoff calls the song "a statement that maybe you can say to make yourself feel better ... as if you were talking to yourself."

It was written around the time that Suze Rotolo indefinitely prolonged her stay in Italy.

The melody is based on the public domain traditional song "Who's Gonna Buy Your Chickens When I'm Gone"[1][2] and was taught to Dylan by folksinger Paul Clayton, who had used it in his song "Who's Gonna Buy You Ribbons When I'm Gone?" As well as the melody, a couple of lines were taken from Clayton's "Who's Gonna Buy You Ribbons When I'm Gone?", which was recorded in 1960, two years before Dylan wrote "Don't Think Twice".

Lines taken word-for-word or slightly altered from the Clayton song are, "T'ain't no use to sit and wonder why, darlin'," and, "So I'm walkin' down that long, lonesome road." On the first release of the song, instead of "So I'm walkin' down that long, lonesome road babe, where I'm bound, I can't tell" Dylan sings "So long, honey babe, where I'm bound, I can't tell".

The lyrics were changed when Dylan performed live versions of the song and on cover versions recorded by other artists.

It has been argued that the guitar on the original version of the song, which features a fast fingerstyle, was played by Bruce Langhorne.[3] In live performances, Dylan often strummed the chords, or flatpicked, but in a similar, fast-paced manner. Moreover, the 1963 "Witmark demos" version of the song has Bob Dylan finger-picking, in a very similar manner to the original 1962 recording. Furthermore, a recording of an April 1963 concert in New York City[4] contains a live version of "Don't Think Twice", finger-picked in a manner similar to that heard on the original recording.

The song was used on the television series Mad Men, Friday Night Lights, and Men of a Certain Age.[5][6] It was also used in Nancy Savoca's 1991 film Dogfight, starring River Phoenix and Lili Taylor; the 2011 film The Help; the October 30, 2016 episode of the TV series The Walking Dead and the January 22, 2019 episode of the series This Is Us (season 3) (episode 11, Songbird Road Part 1).

In the liner notes to the original release, Nat Hentoff calls the song "a statement that maybe you can say to make yourself feel better ... as if you were talking to yourself."

It was written around the time that Suze Rotolo indefinitely prolonged her stay in Italy.

The melody is based on the public domain traditional song "Who's Gonna Buy Your Chickens When I'm Gone"[1][2] and was taught to Dylan by folksinger Paul Clayton, who had used it in his song "Who's Gonna Buy You Ribbons When I'm Gone?" As well as the melody, a couple of lines were taken from Clayton's "Who's Gonna Buy You Ribbons When I'm Gone?", which was recorded in 1960, two years before Dylan wrote "Don't Think Twice".

Lines taken word-for-word or slightly altered from the Clayton song are, "T'ain't no use to sit and wonder why, darlin'," and, "So I'm walkin' down that long, lonesome road." On the first release of the song, instead of "So I'm walkin' down that long, lonesome road babe, where I'm bound, I can't tell" Dylan sings "So long, honey babe, where I'm bound, I can't tell".

The lyrics were changed when Dylan performed live versions of the song and on cover versions recorded by other artists.

It has been argued that the guitar on the original version of the song, which features a fast fingerstyle, was played by Bruce Langhorne.[3] In live performances, Dylan often strummed the chords, or flatpicked, but in a similar, fast-paced manner. Moreover, the 1963 "Witmark demos" version of the song has Bob Dylan finger-picking, in a very similar manner to the original 1962 recording. Furthermore, a recording of an April 1963 concert in New York City[4] contains a live version of "Don't Think Twice", finger-picked in a manner similar to that heard on the original recording.

The song was used on the television series Mad Men, Friday Night Lights, and Men of a Certain Age.[5][6] It was also used in Nancy Savoca's 1991 film Dogfight, starring River Phoenix and Lili Taylor; the 2011 film The Help; the October 30, 2016 episode of the TV series The Walking Dead and the January 22, 2019 episode of the series This Is Us (season 3) (episode 11, Songbird Road Part 1).

Thursday, March 14, 2019

Easy From Now On, Written By Carlene Carter and Susanna Clark, Performed By Emmy Lou Harris

Many songs have been written about leaving a no-good man behind, but few plumb the depths of despair that follow. In this song, Harris lays her heartache down with a clear-eyed understanding of the work that lies ahead. She understands that it will take time (a "month of Sundays") and a change of venue to get over this, and she also knows she is vulnerable, with an empty heart that's easy to fill.

The third verse takes us into rare territory: a one-night-stand where she feels neither shame or triumph - it's just another step on her path to healing, which she explains on her way out:

When the mornin' comes and it's time for me to leave

Don't worry 'bout me, I got a wild card up my sleeve

Carlene Carter and Susanna Clark wrote this song. Carter is the daughter of country music stalwarts June Carter and Carl Smith; Clark (who died in 2012) was the wife of Guy Clark. They each began writing songs in the '70s - Clark composed the 1975 #12 country hit for Dottsy, "I'll Be Your San Antone Rose," and Carter was just getting started on her songwriting journey at the urging of her mother.

By One of the authors of the song:

Wednesday, March 13, 2019

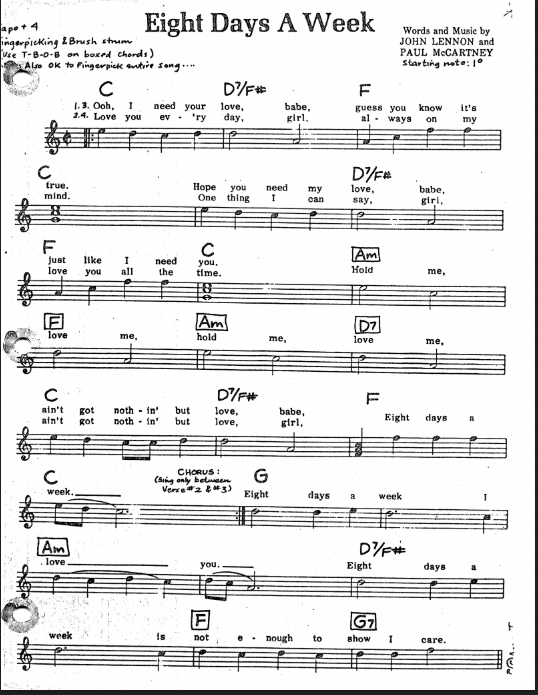

Eight Days A Week, Lennon & McCartney

Inspiration Paul McCartney has attributed the inspiration of the song to at least two different sources. In a 1984 interview with Playboy magazine, he credited the title to one of Ringo Starr's malapropisms, which similarly provided titles for the Lennon–McCartney songs "A Hard Day's Night" and "Tomorrow Never Knows". McCartney recalled: "He said it as though he were an overworked chauffeur: 'Eight days a week.' When we heard it, we said, 'Really? Bing! Got it!'"[3] McCartney subsequently credited the title to an actual chauffeur who once drove him to Lennon's house in Weybridge. In the Beatles Anthology book, he states: "I usually drove myself there, but the chauffeur drove me out that day and I said, 'How've you been?' – 'Oh working hard,' he said, 'working eight days a week.'"[4] In a 2016 interview alongside Starr and Ron Howard, in preparation for the release of the documentary The Beatles: Eight Days a Week – The Touring Years, McCartney reiterated that he had heard it from a chauffeur who was driving him to Lennon's house while he was banned from driving. Starr has said he is not the source of the phrase.[5]

Tuesday, March 12, 2019

Farewell Angelina, Bob Dylan

"Farewell Angelina" is a song written by Bob Dylan in the mid-1960s, and most famously recorded by Joan Baez.

Here Is Dylan's Version:

Monday, March 11, 2019

Fire And Rain, James Taylor

Taylor wrote "Fire and Rain" in 1968. The song has three verses. One is about a friend who committed suicide, another is about Taylor's addiction to heroin, the third refers to a mental hospital and a band Taylor started called The Flying Machine. Each verse is followed by the same chorus, `I've seen fire and I've seen rain. I've seen sunny days that I thought would never end. I've seen lonely times when I could not find a friend, but I always thought that I'd see you again.' James Taylor told me he can't stand to hear his songs on the radio. He dives for the dial if "Fire and Rain" comes on. But it remains a song he likes to sing and one that audiences always wait for.

Sunday, March 10, 2019

Five Hundred Miles, Written By Hedy West

The song is generally credited as being written by Hedy West,[1][2] and a 1961 copyright is held by Atzal Music, Inc.[1] "500 Miles" is West's "most anthologized song."[3] Some recordings have also credited Curly Williams, or John Phillips as co-writers.[4] David Neale writes that "500 Miles" may be related to the older folk song "900 Miles", which may itself have origins in the southern American fiddle tunes "Reuben's Train" and "Train 45".[4][5]..

The most commercially successful version of the song was Bobby Bare's in 1963. His version became a Top 10 hit on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100, as well as a Top 5 hit on both the Country and Adult Contemporary charts.

Other cover versions The song appears on the 1961 eponymous debut album by The Journeymen;[10] this may have been its first release.

The song was heard on the February, 1962 Kingston Trio live album College Concert (a 1962 US #3).

It was further popularized by Peter, Paul and Mary, who included the song on their debut album in May 1962.[11][12] American country music singer Bobby Bare recorded a version with new lyrics, which became a hit single in 1963.[3]

Dick and Dee Dee released a version of the song on their 1964 album, Turn Around.[13]

The song was covered by Sonny & Cher on their 1965 album Look at Us. This version was played over the credits of the 1966 BBC TV film Cathy Come Home.

The lyrics feature heavily in the Bob Dylan song "I Was Young When I Left Home."

The Hooters recorded a version of this song with additional lyrics, dedicated to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. Peter, Paul and Mary provided background vocals for them, as well. This version is on the album Zig Zag.[14]

It has also been recorded by Terry Callier, Lonnie Donegan, the Brothers Four, Glen Campbell, Johnny Rivers, Reba McEntire, Jackie DeShannon, The Seekers, Elvis Presley, Peter and Gordon, Eric Bibb, Hootenanny Singers, Joan Baez, Takako Matsu, Justin Timberlake, The Persuasions and many others.[15] Recently, the song has been recorded by Justin Timberlake, David Michael Bennett, Carey Mulligan and Stark Sands for the soundtrack of the film Inside Llewyn Davis.[citation needed]

The most commercially successful version of the song was Bobby Bare's in 1963. His version became a Top 10 hit on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100, as well as a Top 5 hit on both the Country and Adult Contemporary charts.

Other cover versions The song appears on the 1961 eponymous debut album by The Journeymen;[10] this may have been its first release.

The song was heard on the February, 1962 Kingston Trio live album College Concert (a 1962 US #3).

It was further popularized by Peter, Paul and Mary, who included the song on their debut album in May 1962.[11][12] American country music singer Bobby Bare recorded a version with new lyrics, which became a hit single in 1963.[3]

Dick and Dee Dee released a version of the song on their 1964 album, Turn Around.[13]

The song was covered by Sonny & Cher on their 1965 album Look at Us. This version was played over the credits of the 1966 BBC TV film Cathy Come Home.

The lyrics feature heavily in the Bob Dylan song "I Was Young When I Left Home."

The Hooters recorded a version of this song with additional lyrics, dedicated to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989. Peter, Paul and Mary provided background vocals for them, as well. This version is on the album Zig Zag.[14]

It has also been recorded by Terry Callier, Lonnie Donegan, the Brothers Four, Glen Campbell, Johnny Rivers, Reba McEntire, Jackie DeShannon, The Seekers, Elvis Presley, Peter and Gordon, Eric Bibb, Hootenanny Singers, Joan Baez, Takako Matsu, Justin Timberlake, The Persuasions and many others.[15] Recently, the song has been recorded by Justin Timberlake, David Michael Bennett, Carey Mulligan and Stark Sands for the soundtrack of the film Inside Llewyn Davis.[citation needed]

Saturday, March 9, 2019

Friday, March 8, 2019

Thursday, March 7, 2019

Wednesday, March 6, 2019

Tuesday, March 5, 2019

Monday, March 4, 2019

Sunday, March 3, 2019

Good Time Charlie's Got The Blues, Danny O'Keefe

Everybody's goin' away

Said they're movin' to LA

There's not a soul I know around

Everybody's leavin' town

Some caught a freight, some caught a plane

Find the sunshine, leave the rain

They said this town's a waste of time

I guess they're right, it's wastin' mine

Some gotta win, some gotta lose

Good time Charlie's got the blues

Good time Charlie's got the blues

Ya know my heart keeps tellin' me

"You're not a kid at thirty-three"

"Ya play around, ya lose your wife"

"Ya play too long, you lose your life"

I got my pills to ease the pain

Can't find a thing to ease the rain

I'd love to try and settle down

But everybody's leavin' town

Some gotta win, some gotta lose

Good time Charlie's got the blues

Good time Charlie's got the blues

Good time Charlie's got the blues

(whistling to end)

Saturday, March 2, 2019

Friday, March 1, 2019

Have I Told You Lately That I Love You..Written By Scotty Wiseman, Performed By Rod Stewart..

Myrtle Eleanor Cooper (December 24, 1913 – February 8, 1999) and Scott Greene Wiseman (November 8, 1909 – January 31, 1981),[1] known professionally as Lulu Belle and Scotty, were one of the major country music acts of the 1930s and 1940s, dubbed The Sweethearts of Country Music.

Career Myrtle Eleanor Cooper(Lulu Belle) was born in Boone, North Carolina; Wiseman was from Spruce Pine, North Carolina.

Lulu Belle and Scotty enjoyed enormous national popularity thanks to their regular appearances on National Barn Dance on WLS-AM in Chicago, a rival to WSM-AM's Grand Ole Opry. Barn Dance enjoyed a large radio audience in the 1930s and early 1940s with some 20 million Americans regularly tuning in.

The duo married on December 13, 1934, one year after Wiseman became a regular on Barn Dance (Cooper had been a solo performer there since 1932).

The duo is best known for their self-penned classic "Have I Told You Lately That I Love You?", which became one of the first country songs to attract major attention in pop circles and was recorded by many artists in both genres.

Cooper was the somewhat dominant half of the duo with a comic persona as a wisecracking country girl. Her most famous novelty number was "Daffy Over Taffy". In 1938, she was named Favorite Female Radio Star by the readers of Radio Guide magazine, an unusual recognition for a country performer.

Lulu Belle and Scotty recorded for record labels including Vocalion Records, Columbia Records, Bluebird Records; and Starday Records, in their final sessions during the 1960s reprising their old hits.

They were among the first country music stars to venture into feature motion pictures, appearing in such films as Village Barn Dance (1940),[2] Shine On, Harvest Moon (1938), County Fair (1941) and The National Barn Dance (1944).

The couple retired from show business in 1958, except occasional appearances, going on to new careers in teaching (Wiseman) and politics (Cooper).

Cooper served two terms from 1975 to 1978 in the North Carolina House of Representatives as the Democratic representative for three counties.[3] In 1977, she gave a memorable speech in which she revealed that she had been raped on the country music circuit.[4]

Scotty Wiseman was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1971. After his death in 1981 from a heart attack in Gainesville, Florida, Cooper married Ernest Stamey in 1983; and in 1989 recorded her first album in 20 years for a small traditional music label, Mar-lu Records out of Portageville, Missouri.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)